July 30, 2024

More modern cheesemaking was created by rural folks; the steps to make it are delicious dairy science

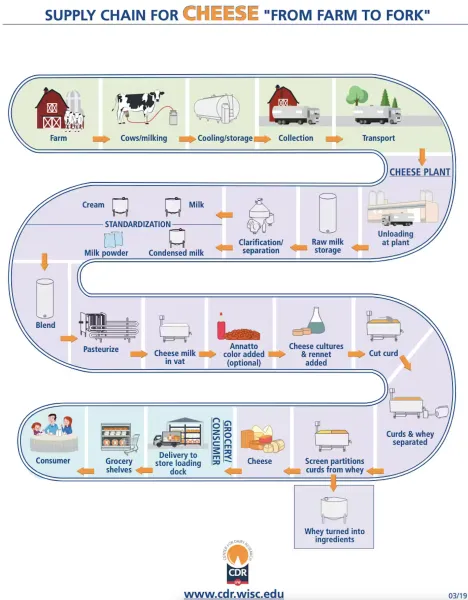

Dairy cheese all starts will milk and is transformed from there.

Even though cheesemaking history formally dates back to 2500 BC, the more traditional cheesemaking we know today was invented by French peasants. If you know how rural communities work, you're probably not shocked that farming folks from centuries ago were brilliant and creative in using milk for delicious ends.

Fast forward to the present day, and we now know what rural cheesemakers used to develop cheese is pure science, writes John A. Lucey for The Conversation, a journalistic platform for academics. Lucey, a food scientist who has studied cheese for 35 years, takes readers through the cheese-making process from milk to mozzarella. A few edited steps are shared below.

First off, cheese has delightfully few ingredients. "It’s made with milk, enzymes – these are proteins that can chop up other proteins – bacterial cultures and salt. Lots of complex chemistry goes into the cheesemaking process, which can determine whether the cheese turns out soft and gooey like mozzarella or hard and fragrant like Parmesan," Lucey notes. "All cheesemakers first pump milk into a cheese vat and add a special enzyme called rennet. . . . The cheesemaker is essentially turning milk from a liquid into a gel."

Churning milk and rennet into gel can take 10 minutes or more depending on the cheese. The cheesemaker will then cube the gelled "curd" and work to remove moisture from the smaller blocks. "To do so, the cheesemaker might stir or heat up the curd, which helps release whey and moisture," Lucey explains. "Depending on the type of cheese made, the cheesemaker will drain the whey and water from the vat, leaving behind the cheese curds."

Cheesemakers add different ingredients and steps depending on the type of cheese being made. Hard and soft cheeses require different treatments. For example, "mozzarella, [is placed] in a salt solution called a brine. The cheese block or wheel floats in a brine tank for hours, days or even weeks," Lucey writes. "During that time, the cheese absorbs some of the salt, which adds flavor and protects against unwanted bacterial or pathogen growth."

As cheesemakers go through each step "several important bacterial processes are occurring," Lucey adds. Even as a finished product, cheese is "a living, fermented food. . . .Cheesemaking is a milk concentration process. Cheesemakers want their final product to have the milk proteins, fat and nutrients, without as much water. . . .There are hundreds of different varieties of cow’s milk cheese made across the globe, and they all start with milk. All of these different varieties are produced by adjusting the cheesemaking process."

To read more about the science of making cheese, click here.