July 19, 2024

Reviving a native coastal hay could be the solution for farmers experiencing saltwater intrusions on their land

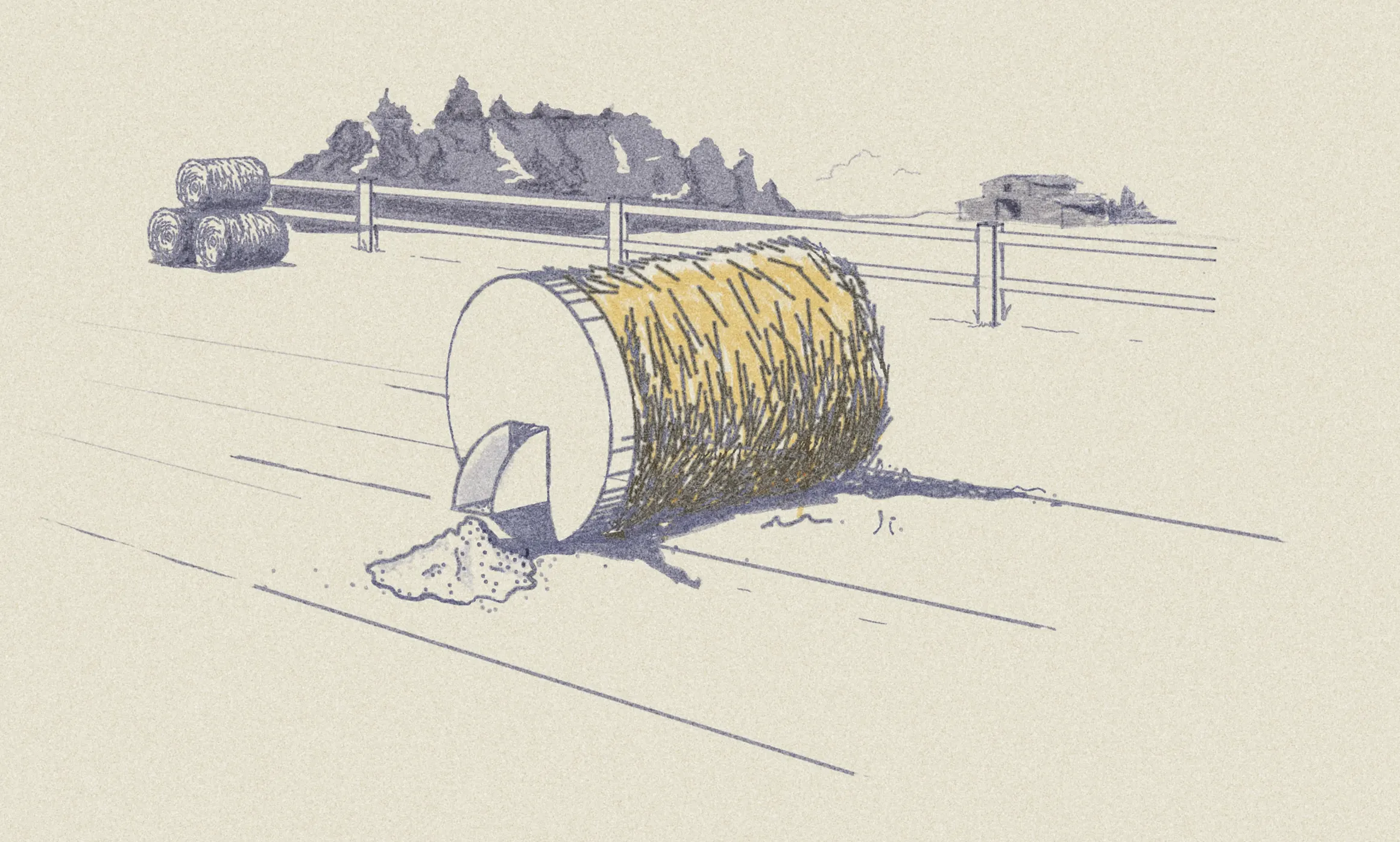

Salt hay is naturally weed-free and rot resistant. (Graphic by Adam Dixon, Ambrook Research)

As saltwater intrusion occurs more frequently along U.S. coasts, regional farmers are losing part of their livelihoods to ground that is too salty for many traditional crops. In seeking out a solution, some farmers are working to bring back a native hay species that thrives in salt. "Farms at the low, marshy edges of the East Coast are rapidly losing ground as rising sea levels push salty water further into the fields, reports Kate Morgan of Ambrook Research. "American growers are beginning to see their own opportunities in reviving a historic salt hay industry."

Spartina patens -- more commonly known as "salt hay" -- was grown along U.S. coastal borders beginning during colonial times through the end of the 1900s. The perennial cordgrass hay can be "used for animal fodder, as a building insulator, packing material, or turned into paper," Morgan explains. "It’s incredibly easy to grow, but equally difficult to harvest. It performs best in marshy areas close to the water, which meant farmers had to cut it by hand, using horses and oxen to haul it out, or loading it onto rafts. By 1945, tractors had officially overtaken horsepower on American farms, and marshes and machinery don’t mix."

While farmers love a crop that is naturally weed-free, self-seeding and rot resistant, not being able to harvest it with modern equipment presents a challenge. Atlantic-coast farmer John Zander, whose Cohansey Meadows Farms has some significantly salty soil, has been experimenting with salt hay production methods. "His fields, planted just a bit further inland than the grasses might typically grow, are producing prolifically," Morgan writes. "He cuts, bales, and sells some for mulch, bedding, and fodder, and he hopes increased supply will help reinvigorate the various markets for salt hay. But his main goal is to sell transplants to other coastal farmers."

Zander noticed his salt hay crops had added benefits. He told Morgan: “The root mass is just so dense and thick. It just really grips on. I think if we can get some of that into places where we’re having erosion problems, it might be pretty beneficial to some of these coastal farms and towns.”